The Daintree. Ironically, an increasingly well known natural World Heritage area, yet, named after a forgotten individual whose amazing achievements have faded into obscurity.

Visitors to the region – and even locals – often ask questions like “Where exactly is the Daintree?” and “’Who was Daintree anyway?”

Is “Daintree” the village, the River, the National Park, an old Shire Council or an obscure mountain in the Gold Rush region of Palmer River? Yes, it’s all of these, plus a few more.

So, who was “Mr Daintree” and what is his legacy?

We’ll try to fill a few gaps – to paint the canvas a little.

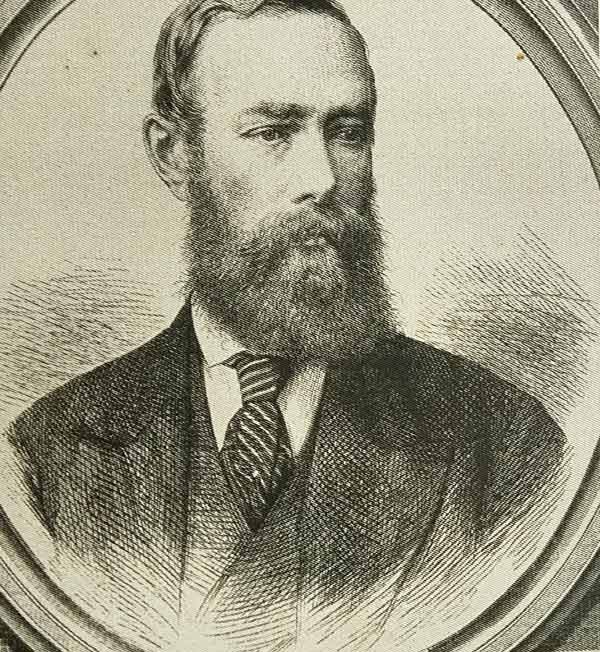

Richard Daintree – The Person

In 1832, Richard Daintree was born in Huntingdonshire in the UK, and died in 1878, aged 46 years. His short life was busy and productive thus his wonderful legacy, but strangely left no legend to speak of. The person and his life have been forgotten.

He was clearly an outstanding individual, a pioneer and a visionary. While he was recognised by his adopted State – Queensland – nationally and internationally, he has scarcely been seen as an important part of our local heritage within the Douglas Shire community.

Perhaps it’s because Richard Daintree himself never actually visited any of the many places that bear the name Daintree.

These include a Shire (yes there was a Daintree Shire), a mountain (Mt Daintree), a set of reefs (Daintree Reefs), a River, a village, a National Park (in two sections!), and a Coastline all named in his honour.

Oh, not to forget a fossilised fern from the New South Wales coalfields, the Taeropterius Daintree, and a Queensland wattle Acacia Daintreeana (aka Excelsa).

In his professional area of geology/metallurgy, he helped improve and move the mineral exploration focus in Australia away from palaeontology towards geology/metallurgy. While he was only an occasional prospector himself, he paved the way for the discovery of significant coal deposits in New South Wales, plus many gold discoveries throughout north Queensland, including the Etheridge and the Palmer River.

Daintree also pioneered the use of field photography in geology/metallurgy. Incredibly, he and his horses lugged a ridiculously cumbersome load of slides, chemicals and photographic equipment around north Queensland. In so doing, he recorded invaluable images of early Indigenous contact, and colonial life.

Richard Daintree’s Journey

Daintree first came to Australia in 1853 at age 21 years, no doubt to escape the cold and miseries of England. He first tried his hand, unsuccessfully, prospecting on the Victorian Goldfields.

Driven by financial need, commonsense and a desire for respectability he became a successful assistant surveyor in Victoria. He then returned to England to further his studies in Geological Surveying and photography. He returned to Victoria in 1857, married to his charmingly named wife (nee Lettice Foot) in 1857. variously combining a business interest in photography with full time Government surveying employment.

He was funded by the Victorian Government to do a photographic tour of the Goldfields for an International Exhibition in London in 1860. He won two medals –one for photographs of rocks and fossils, the other for his more generic photographs of Victoria.

In 1863/64, Daintree and his young family (eventually two sons and 6 daughters) answered the pioneer call and took up the “Maryvale” pastoral lease in partnership with the famous Hann family on the Upper Burdekin River in Queensland.

With William Hann, he made geological, pastoral and photographic forays into North Queensland between1866 and 1869.

But a new challenge was on the horizon.

Queensland’s First Financial Crisis

A few years earlier in 1859, the new Queensland colony had been created – acrimoniously – and was left with a bereft Treasury. The very hurt and mean-spirited New South Welsh Government left the fledgling State with just 7 ½ pence in its Treasury coffers. This was later stolen! True!!!

Thus the Great Queensland Imperative commenced! Develop or perish! And let nothing get in the way.

Queensland quickly realised it needed development to build up the miserable coffers. This meant exploiting farming and minerals. Richard Daintree convinced them that efficient exploitation first required proper exploration, and that he was just the person to do it! And he was.

Discoveries and Recognition

Daintree was appointed as the Queensland Government Geologist, Northern Division, in 1868. He and his team found good indications of gold at the headwaters of the Gilbert River and at Georgetown, originally known as Etheridge.

In his role, Daintree sent about 300 botanical fossil samples to Ferdinand von Mueller at the Royal Melbourne Herbarium. Von Mueller acknowledged Daintree by naming a species of wattle Acacia Daintreeana.

He even found fossilised bones of the Diptrotodon, one of perhaps nine species of megafauna wombats. Not just a megafauna but a megaherbivore! It was almost certainly a migrating megaherbivore. When you think Diptrotodon, think of a Giant three ton wombat, the size of a hornless rhinoceros, browsing on the grassy plains west of the Great Dividing Range.

Today, you can see a Diptrotodon at the Daintree Discovery Centre, just north of the Daintree River.

Exhibitions and Legacies

Daintree and family returned to London in 1870.

Recognising his scientific and business status, the Queensland Government asked Daintree to put together an exhibition of photographs and mineral specimens for the 1871 Exhibition of Art and Industry in London. Unfortunately Daintree’s mineral samples were lost in a shipwreck on the way to London, and Daintree had to create the Exhibition using his photographs and maps, plus borrowed fossils from a colleague. So, presumably no Giant Wombat fossil was on display in the UK! Nevertheless, his dioramic scenes and cleverly curated displays were considered innovative and “displayed distinctive new spatial experiences for international audiences”.

International exhibitions were enormously popular in those days and Daintree’s work attracted both money and migrants to the point that he was appointed Queensland’s London-based Agent-General for Emigration from 1872 to 1876.

Daintree’s collection of over 200 photographs was shown at 10 International exhibitions including between 1871 (London), Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876), Paris (1878), Sydney (1879) to a final commemorative one in1897 (Brisbane), after his death. The collection showcased landscapes, geological formations and people from across Queensland in the 1870s, and was particularly focused in the north of Queensland and on mining and agricultural endeavour.

A little scandal. Regrettably, the Premier of the day was unimpressed with the overall quality of the immigrants, and the finances of Daintree’s office, so in 1876 he took a sea voyage to England to investigate, and sacked several staff. Daintree himself was considered blameless and was made a Companion of St Michael and St George in the same year, 1876.

All this without a Crimes Commission! Just the power of a Queensland Premier, and a sign of improved State finances.

Despite the bestowed honours, Daintree resigned, and with the business trauma and his ongoing ill-health spent two winters recuperating in the south of France. Richard Daintree died in Kent in1878 aged 46 years, nominally of tuberculosis.

Those photographic slides that amazed Britain and Europe have become a key aspect of Australia’s heritage. The slides today live on scattered in the Oxley Memorial Library in NSW, the Queensland Museum and the National Museum of Australia in Canberra, the latter with a dedicated semi-permanent exhibition on display.

Daintree Naming Add-ons

Oddly, Richard Daintree never actually visited either the gold-bearing Palmer River or the Daintree River.

It was William Hann that explored the Palmer in 1872 and named Mt Daintree in the Palmer River area, after his friend and neighbour following Daintree’s return to England as Agent-General, In 1873, Mulligan found gold around Mt Daintree, setting off the Palmer River goldrush.

Daintree’s friend and fellow geologist, George Dalrymple, on his epic voyage through FNQ in 1873, visited the mountainous jungle country around Mossman and the Bloomfield River area and named the Daintree River.

A year after Richard Daintree’s death in 1879, an expanse of land to the west around the Palmer River, including Mt Daintree, was named the Daintree Shire in his honour. The Daintree Shire survived 40 years, until 1919 when the Daintree and Hann Shires and the Town of Cooktown were amalgamated to form the Cook Shire, now based in Cooktown.

Formal recognition of Daintree Village came in 1879, again a year after Daintree’s death, and coincided with the establishment of the Douglas Shire (1880?).

Forward 100 years. By 1981, when the new National Park around the Daintree River was searching for an identity, calling it “Daintree” was a no-brainer. The Park comprises two sections. The larger but less accessible is behind Mossman and the mountains, and the second – the jewel in the crown of the Daintree – along a Daintree Coast strip from the Daintree River to Cape Tribulation and the Bloomfield river.

Hence, the latest namings in honour of Richard Daintre – the Daintree Reefs and Daintree Coast.

Footnote – Early Wet Plate photography – 1855 onwards

Early photography involved a wet plate process. It was tricky and cumbersome, especially in the field on a geological expedition.

The negative would be developed on a glass plate coated in gun cotton or colloidon (a gummy, creamy emulsion made by dissolving cotton wool or wadding in nitric or sulphide solutions.

A photographer would throw a few crystals of nitrate of silver into a dish; dissolve them with a cup of water; then place one of the colloidon coated plates into this sensitising solution for a few seconds.

The plate was then inserted in a special little carrier, taken to the camera, exposing the subject for 5 seconds, then returned it to the dark room and developed immediately while it was wet. The very moment it dried, it was useless – so try again!

All world photos taken between 1855 and 1880 used this process.

Even with packhorses, Richard Daintree had a huge task just transporting and achieving the finished products. Cameras, tripods, glass slides, bottles of expensive and dangerous chemicals, a tent as dark room…. and the list goes on.

Photography was a breakthrough in many areas, including geological surveying. Despite the complex process, it was still quicker and more accurate than drawing by hand. Daintree’s special flair made field-photography both serve his profession as a tool for research and to generate interest and publicity.

Where? What? Why? Who is the Daintree? Does it all make sense now??

The Daintree name clearly lives on in the Douglas Shire. Yet, it barely reflects the man’s achievements and legacy!

Perhaps, one day, we might again explore and exploit the Daintree legacy and find ways of representing his impressive work.

Mike D’Arcy

D’Arcy of Daintree

Mike spent many years as an interpretive Wet Tropics Tour Guide running his own business D’Arcy of Daintree 4WD tours. Now retired. Mike has a wealth of knowledge on the Daintree Coast region and continues to share this via his audio tours and blog posts on the Daintree Coast website.

The Daintree Coast website is your guide to this amazing region. Browse our website for local insight, history and visitor guides to local destinations. Explore our directory for activities and things to do, see and experience. Find Daintree Rainforest accommodation, cafes and restaurants and must-see places.

Daintree Coast – Be Amazed.